Again And Again And Again

First published in Our Jackson Home

The Valarie Spragins School of Dance, located in Bemis, Tennessee – just south of downtown Jackson – began in 1986 as a once-a-week class with eight students who met at the local community center. Valarie had been dancing since grade school and working as an instructor at a studio in Jackson for ten years. When she was nine months pregnant with her second child, she decided to give up teaching, never intending to go back. Then one day, a neighbor asked if she would teach a class again. What started out as eight students became 24 that fall, and by the next year, she had over 50.

With the consistent growth, it became time to find a location of her own. Valarie moved her classes to a little studio by Southside High School – a building many locals will recall as having once displayed a massive mural of ballet shoes on the exterior wall. For the next 19 years, this is where she would hire additional instructors and teach her students, several of whom she would later hire as instructors themselves.

Courtney Vandiver, Veronica Sesson and Polly Robison began taking lessons at Valarie’s studio as elementary-age children. There was a period of time when Courtney had stopped taking classes. She said she remembered coming back and feeling overwhelmingly behind in her skill level. So for hours, Valarie would sit on the studio floor with a cigarette in one hand and a composition notebook in the other, drilling Courtney on French ballet terminology and techniques to help her catch up with the other students. Courtney said that during this time in her life, the dance school provided a much-needed sense of structure and security.

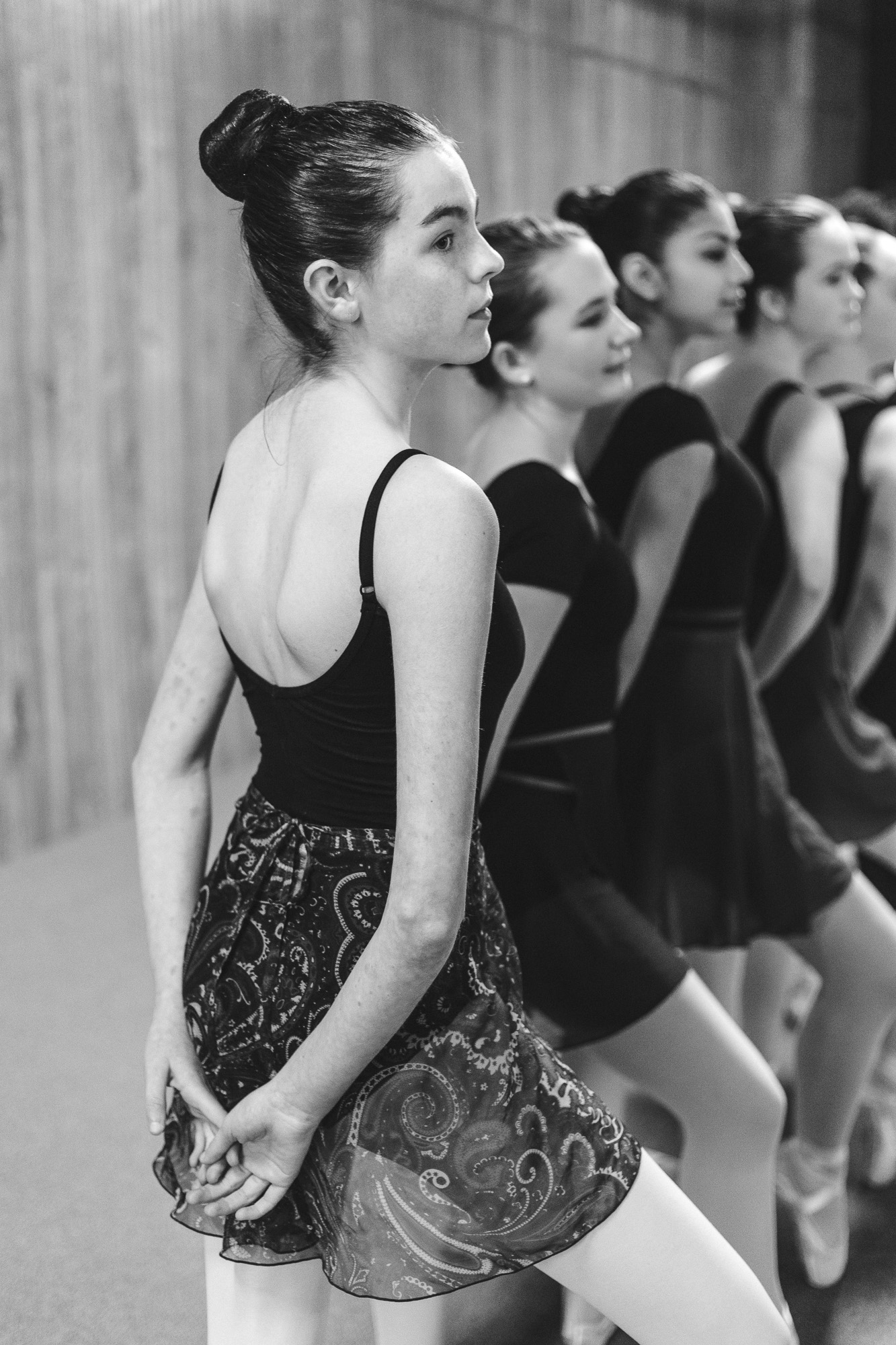

“We tell our students very young that a dancer is not trained overnight. If you truly want to be a dancer, it’s a lifelong commitment,” Valarie said. “You’re going to put in 15 years here and then go on somewhere else.”

In a small area such as South Jackson, the same families have lived together for generations, and people don’t often leave. The benefit is a deep sense of community and belonging. A downside, though, is the lack of exposure people have to experiences outside of that community. Valarie was first introduced to the world of dance in elementary school when her friend Wanna Martin’s mom brought Valarie to her daughter’s dance class. The friend’s mom was the one who convinced Valarie’s mom to let her take lessons.

“I was exposed, and once I was exposed, I was hooked,” Valarie said. “But a lot of my friends weren’t exposed to it. There was nobody I had much in common with.”

People in the community were committed to and invested in their public school system, because the schools their kids attended were the same schools the parents and grandparents and great-grandparents attended when they were growing up. Activities such as dance that weren’t based in the school system felt foreign to a lot of people, almost a betrayal.

While it has been difficult teaching the art of dance in rural West Tennessee, Valarie knew that if she could get buy-in from her community, it would be more than just a dance studio – it would be a family.

The instructors admit that it’s not easy teaching dance in this area, where they seem to always be competing with softball for the girls’ time and interest. But it’s worth it, because as Courtney says, “I’m shaping lives, not dancers.”

Many people who live in North Jackson or Midtown tend to stay away from South Jackson and Chester County and Bolivar. They hear rumors of a high crime rate and don’t venture far past the fair grounds. But Valarie says that what outsiders assume is not what the locals experience. To them, it’s a quiet place packed with decades of memories, and they don’t want any of that to change. To some extent, they don’t mind the assumptions that keep people at a distance, because maybe if fewer people want to come visit, there won’t be as much change.

“We get a bad rap, but it’s a nice place to live,” Valarie said. “Only people who have never experienced this kind of community wouldn’t know where to look for it.”

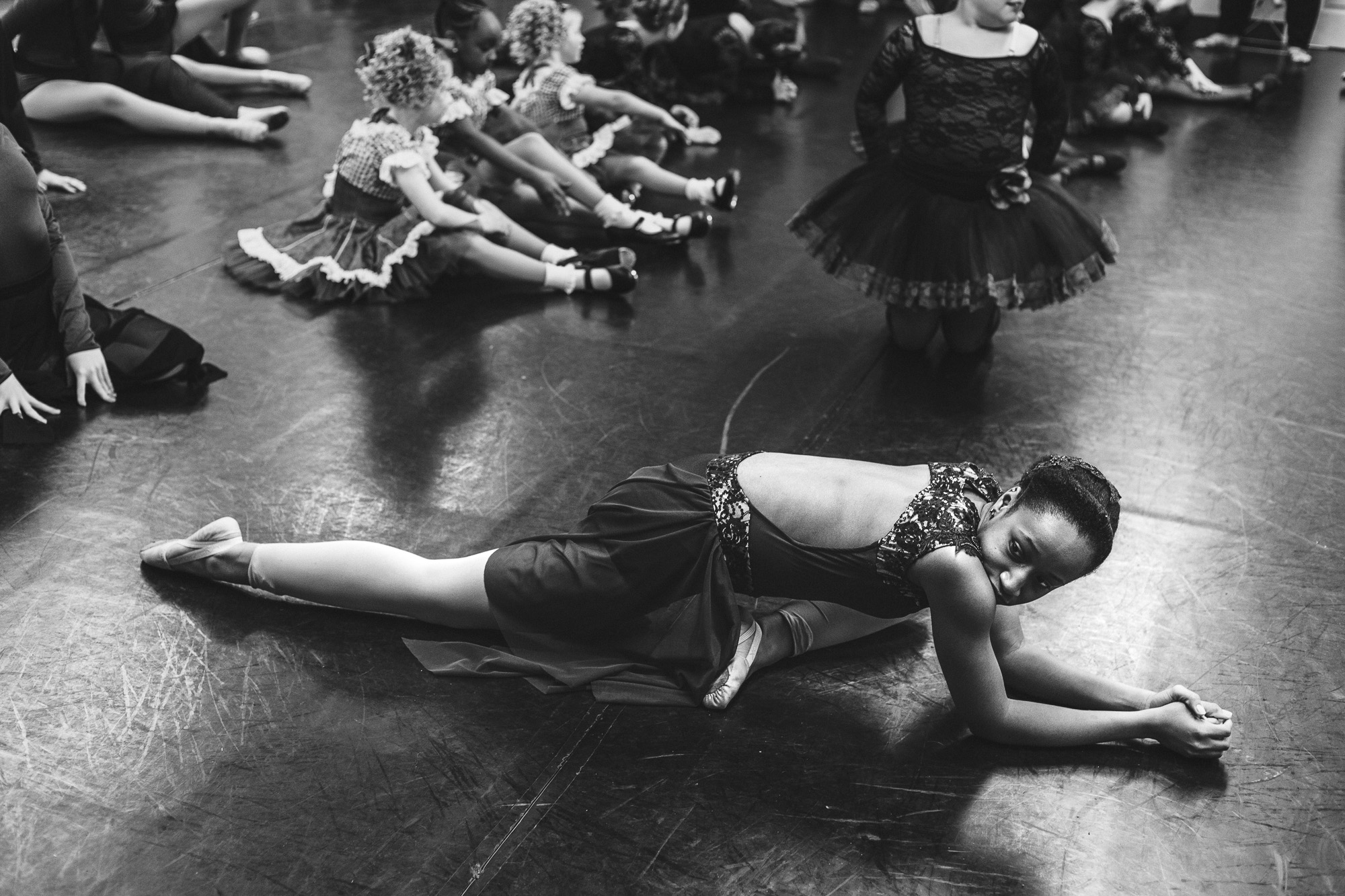

People often wonder what keeps these girls coming back, week after week, month after month, year after year. It’s not easy, and there comes a time for each dancer when she wants to quit, when progress feels slower than it’s ever been, when she’s sick of doing it all again and again and again and getting what seems to be no return for the effort. But the dancers find a reason to stay that’s more appealing than the temptation to quit.

“If the parents have to push them to come back, it doesn’t last very long,” Valarie said. “The kids who don’t love it enough to perform don’t last. The first time I stepped out on a stage, I was hooked. I was a very shy child, but the stage was a different place. On the stage, I could be someone else.”

Some people go a lifetime without ever really encountering the best version of themselves. With dance, many of these girls have been able to discover and develop themselves from a young age and experience the reward of hard work. So, they come back and they keep dancing – week after week, month after month, year after year, again and again and again – because at the end of the day, it’s about more than dancing.